As User Experience designers, one of the most important parts of our role is testing products and services with our users. This part of the design process is essential, as we need to find out if what we’re creating is usable and, if not, we need to understand how we can make it better.

Before we went into the first lockdown in March, our main method of user research and testing was Guerrilla testing, where we would go out and speak to residents in places such as cafés, museums and libraries, to test anything from early ideas to fully functioning prototypes. It’s cost effective and allows us to get instant feedback and make changes quickly.

However, for our recent flooding project, COVID-19 restrictions meant that Guerrilla testing wasn’t an option, so we had to find a way to conduct remote testing sessions that would give us qualitative feedback on the new ‘report a flood’ online form and map as well as testing the user journey of the form.

What is remote user testing?

In a previous blog we have talked about Lookback, a user testing recording software we sometimes use. Lookback allows us to record remote user testing. We send the participant a link with a task to complete and the user participates by themselves with no-one else present during the session. This is known as an unmoderated remote session. We then watch the recording of the session and analyse their actions and feedback.

The main drawback with an unmoderated session is that we can’t ask or answer queries during the session, so we needed to make the session as easy as possible for participants to set up and complete by themselves. As a vital part of user testing is encouraging participants to think aloud and talk about what they’re doing as they complete the task, we needed to make this a clear part of the instructions. Being able to listen to participants whilst watching what they’re doing on screen helps us to understand what changes need to be made.

Recruiting participants

The first issue we faced was recruiting participants. Before the pandemic, when we conducted Guerrilla user testing, we would find participants on the day. Recruiting participants during the pandemic added new ethical challenges for the team. We were especially mindful that potential participants may have been experiencing high levels of distress or anxiety. Many front-line service staff were working under a great deal of pressure and we needed to consider whether our user testing could create an additional burden on them. We asked our friends and families for volunteers for user testing and gradually we narrowed down a pool of users to participate in user testing. As our first foray into remote user testing this enabled us to gather some insights, but we can’t rely on this method going forward as insights could be biased, and we also can’t guarantee a mixture of demographics.

Consent and ethics

Once we had a group of participants, we had to securely gain their consent remotely and digitally which meant adapting our original physical paper consent form, formerly signed by the participant on the day of testing. Working with the Information Governance team, we created new instructions and a new consent form. These were emailed to participants who had to reply to the email, stating their name and if they consented to both screen and audio recording during the remote user testing session. We used a secure email inbox to communicate with participants. To avoid additional ethical issues, we did not allow user testing participants to use their cameras during the testing.

As we wouldn’t be able to advise, or answer any questions or concerns from the participant during testing, we created an in-depth set of instructions which were emailed to the participant prior to the session. To reduce the risk of any GDPR issues, we included fake contact details to be used to populate fields in the form that was being tested, so they did not enter any personal details.

The instructions also asked participants to turn off notifications to avoid any sensitive and personal ‘pop-ups’ from notifications. We added a clause to our consent form to ensure participants knew they could contact the council to delete the recording if anything appeared on the screen that they didn’t want recording.

As a team we had to carefully balance the numerous ethical issues and factors against the fact that research could prevent us developing a poorly designed service that would create additional problems for users. We made informed decisions and were in close contact with the Information Governance team when creating every aspect of this remote process.

Creating the instruction guides

To guide the participants through the remote unmoderated user testing without any of our digital team being present, we had to create a set of step-by-step instructions including setting up Lookback, testing the form and ending the session.

We needed to be inclusive to different devices as we were unable to provide participants with a device to test on. We created a desktop, Android and Apple Lookback unmoderated user testing guide. All three of the guides were emailed out to each participant with the instruction of selecting the correct guide for the device being used to take part in the testing. We created these guides by documenting and explaining each step that the participant would need to go through to complete the testing.

When running a Guerrilla user testing session, we would usually script questions to go through with the user, alongside a list of instructions to aid the participant to get through the form. Instead, we had to embed these scripts and instructions into Lookback and hope that the participants used them.

Included in the Lookback welcome message, which is shown to participants when their session first starts, was a brief explanation of what we were testing and why, further information about how the prototype would look and work and a reminder to talk and explain their thoughts as they participated in the session.

Testing different user journeys

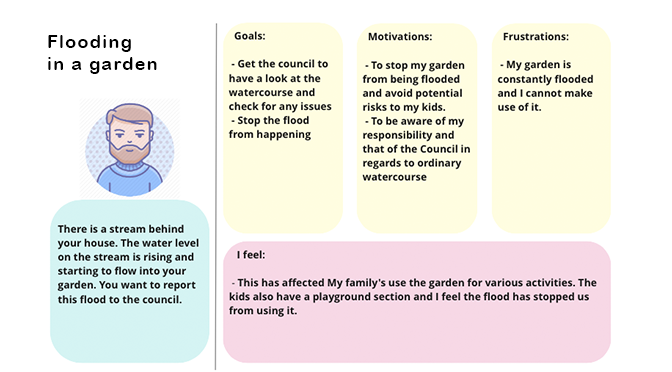

In a previous workshop we had created seven personas, each requiring a different service, and therefore a different journey through the flooding form. We based each Lookback session on these personas, allocating them at random to the participants in the user testing session, with each given a different task to take them through a unique journey in the flooding form.

Task example: ‘high water levels’

The user was given the following scenario and asked to complete the form:

“You walk by a river to get the bus to university. You’ve noticed that the water on the river is very high and you think it might be about to flood. This could affect your journey to university if it does flood. You want to report this to the council.”

Giving the participants a scenario allowed them to answer questions in the form, without providing them with direct answers or instructions. This gave us an awareness of whether the options are clear and understandable to the participant conducting the user testing. It also allowed specific areas of the form to be tested, such as the question “Where is the flood coming from?” The participant had to decide which option they think suits their scenario.

In part 2 of this blog, we’ll be discussing how we analysed the user testing feedback and how we could improve our process for conducting unmoderated remote user testing.

For regular updates from the #DigitalStockport blog sign up for email alerts.